por Francisco García Bazán (Universidad A.J.F. Kennedy-CONICET)

Ex: http://culturatransversal.wordpress.com/

Al final de mi libro en colaboración René Guénon y la tradición viviente (1985), apuntaba algunos rasgos sobre la influencia de René Guénon en una diversidad de estudiosos contemporáneos. Allí escribí:

«El mundo de habla española, por su parte, se abre velozmente en los últimos decenios a la gravitación guenoniana. Hemos de reconocer que la Argentina, en este sentido, no sólo ha jugado un papel preponderante, sino que incluso fue oportunamente una verdadera precursora de este florecimiento del pensamiento de Guénon [en la geografía hispana].

Ya en 1945 se publicó en Buenos Aires la Introducción general al estudio de las doctrinas hindúes y la crítica periodística porteña recibió favorablemente la novedad de [la presencia] de un credo de inspiración tradicionalista [en la cultura francesa]. A esta traducción siguieron en años sucesivos: El teosofismo (1954), con varias ediciones, La crisis del mundo moderno (1967), Símbolos fundamentales de la ciencia sagrada (1969 y El esoterismo de Dante (1976). Mucho más reciente, [por el contrario], es el interés de los españoles por nuestro autor. Pero aunque la traducción de la primera de las obras citadas es de la década del 40, la evidencia de una lectura y conocimiento del autor francés ya se reflejó con anterioridad en individuos y grupos de intelectuales argentinos.

Los primeros que demostraron interés por el pensamiento de R. Guénon en nuestro país fueron pensadores del campo católico, hondamente preocupados por la esencia y el futuro de la nación. Se agruparon en Buenos Aires y Córdoba, en torno a las revistas Número y Sol y Luna, y Arx y Arkhé, respectivamente. Entre estos [escritores] por la influencia y uso que hicieron de las obras de Guénon sobresalen: César Pico, José María de Estrada y, muy probablemente, el poeta Leopoldo Marechal –todos ellos en Buenos Aires y vinculados a los Cursos de Cultura Católica-. En la Provincia mediterránea, Fray Mario Pinto y Rodolfo Martínez Espinosa, autor [este último] del primer artículo escrito en la Argentina sobre nuestro pensador [tradicional] y su corresponsal [con un intercambio de correspondencia entre los años 1929 y 1934], cuando Guénon residía en El Cairo. [Las dos cartas del autor franco-egipcio son del 24 de agosto de 1930 y del 23 de febrero de 1934. La última es una larga misiva de ocho carillas, en la que a las dudas expuestas por Martínez Espinosa responde Guénon condensando en ella la doctrina tradicional y anticipando incluso soluciones sobre las diversas vías espirituales, que posteriormente hará públicas. Estas cartas fueron primeramente publicadas por mí traducidas al castellano el domingo 13 de julio de 1980 en el Suplemento Literario de “La Nación”, cuando era dirigido por Jorge Emilio Gallardo, posteriormente fueron publicadas en edición bilingüe en el libro al que nos estamos refiriendo y poco después aparecieron en Francia en Les Dossier H René Guénon, dirigido por Pierre-Marie Sigaud, editado por L’Age d’Homme, Lausana, 1984, 286-289, gracias al contacto del que tomó la iniciativa André Coyné]…El ilustre filósofo de la ciencia, Armando Asti Vera, ofreció al público hispanohablante en 1969 una elegante y correcta primicia sobre la vida, obra y filosofía de Guénon de amplísima difusión. La casi totalidad de su obra escrita y de dirección docente llevan el sello indeleble del pensamiento guenoniano que frecuentaba desde su madura juventud» (pp. 171-172 y notas).

Lo dicho se refiere a nuestro país y medio cultural, pero en ese mismo libro, páginas más adelante, hacíamos referencia a la influencia de René Guénon en investigadores franceses, judíos e indios, sobre todo en el gran especialista en Shankara, T.M.P. Mahadevan, en cuya tesis sobre Gaudapâda. A Study in Early Advaita (University of Madras, 1975), el tradicionalista nacido en Blois está a menudo citado y es altamente reconocido por su profunda comprensión del Vedânta advaita o no dual. En esa ocasión, sin embargo, apenas nos habíamos referido a Mircea Eliade. Pero, posteriormente, y después de haber leído el artículo del profesor rumano, «Some Notes on Theosophia perennis» publicado en la revista de la Universidad de Chicago History of Religions (1979), pp. 167-176, nuestra opinión cambió y admitimos la influencia de Guénon en su obra como historiador de las religiones. Posteriormente hemos comprobado que un investigador particularmente calificado en el conocimiento de la vida y obra de Guénon, como lo es Jean-Pierre Laurant, de L’ École Pratique des Hautes Études. Section Sciences des Religions, escribe en el Diccionario Crítico del Esoterismo, dirigido por Jean Servier, publicado en 1998 por P.U.F. y recientemente traducido por la Ed. AKAL al castellano, en la entrada correspondiente a “René Guénon”, que firma: «También desempeñó [Guénon] un papel muy importante [lo subrayamos] en la formación del pensamiento de Mircea Eliade e influyó sobre el conjunto de la renovación de la historia de las religiones, hasta tal punto que Gaétan Picón lo integra dentro de su Panorama des idées contemporaines (1954). Su influjo [en esta dirección] se prolonga, hasta nuestros días, a través de una renovada reflexión sobre el simbolismo, la “Tradición” y las tradiciones en los trabajos de J. Borella en Francia, R. Martínez Espinosa y F. García Bazán en Argentina o, en Estados Unidos, en los de Joseph E. Brown sobre los indios» ( Vol. I, p. 754). [Permítaseme hacer la aclaración en paralelo que respecto del cultivo de los estudios sobre Guénon en nuestro medio y la recepción de su pensamiento, también Piero Di Vona, profesor de la Universidad de Nápoles y autor de un respetable libro sobre Evola e Guénon. Tradizione e civiltà (1985), en su ponencia sobre “René Guénon e il pensiero de destra”, presentada en la Università degli Studi di Urbino, a fines de los 80’, ya reconocía asimismo en confrontación con el desarrollo de la teología de la liberación sudamericana, que frente a ella: «Tutte queste osservazioni rivestono almeno per noi una grande importanza perché nell’attuale cultura sudamericana Guénon è oggetto di attento studio in ambienti qualificati. (Rimandiamo al libro di F. García Bazán, René Guénon y la tradición viviente, etc.)»].

Pero más recientemente todavía y con motivo de la publicación consecutiva de las Memorias de Eliade, la perspectiva sobre la irradiación guenoniana se ha ampliado y así hemos tenido la oportunidad de leer un erudito artículo del estudioso italiano Cristiano Grottanelli, bajo el acápite de «Mircea Eliade, Carl Schmitt, René Guénon, 1942», en la Revue de l’Histoire des Religions Tome 219, fascículo 3, julio-septiembre 2002, pp. 325-356, que arroja nuevas luces y sombras sobre la cuestión claramente anticipada en el título y que amplia el panorama con la mención del gran jurista y experto en derecho internacional, Carl Schmitt, tan apreciado en los comienzos de los años 30 por el régimen nacionalsocialista, como posteriormente repudiado tanto por la SS y el nazismo que representaban, como por sus vencedores aliados.

Pero más recientemente todavía y con motivo de la publicación consecutiva de las Memorias de Eliade, la perspectiva sobre la irradiación guenoniana se ha ampliado y así hemos tenido la oportunidad de leer un erudito artículo del estudioso italiano Cristiano Grottanelli, bajo el acápite de «Mircea Eliade, Carl Schmitt, René Guénon, 1942», en la Revue de l’Histoire des Religions Tome 219, fascículo 3, julio-septiembre 2002, pp. 325-356, que arroja nuevas luces y sombras sobre la cuestión claramente anticipada en el título y que amplia el panorama con la mención del gran jurista y experto en derecho internacional, Carl Schmitt, tan apreciado en los comienzos de los años 30 por el régimen nacionalsocialista, como posteriormente repudiado tanto por la SS y el nazismo que representaban, como por sus vencedores aliados.

El período más difícil de determinar en la vida de Eliade es el que va de los años 1934, cuando ya ha residido tres años en la India (1929-1931) dirigido por el eminente profesor de filosofía hindú Surendranath Dasgupta, y ha cumplido prácticas de Yoga en Rishikesh, en el Himalaya, en Svargashram con Swami Shivananda. Vuelto a Bucarest ha publicado la novela Maitreyi de gran éxito de ventas (1934) y ha presentado hacia fines de año su tesis de doctorado sobre la filosofía y prácticas de liberación yóguicas como una perspectiva dentro del pensamiento indio, siendo nombrado asistente de Naë Ionesco, profesor de Lógica y Metafísica en la Universidad de Bucarest. Desde esa fecha hasta fines de 1944 en que fallece su esposa Nina Mares y en que al año siguiente (1945) establece relaciones culturales y esporádicamente docentes en París como exiliado con el apoyo de la colonia rumana y colegas y amigos como Georges Dumézil, su biografía es bastante movida y es también durante ese período en el que apoyado en su formación de indólogo incipiente, se cimentó asimismo su método e ideas como teórico de las religiones. Después que obtiene la adjuntía de cátedra a través de su titular Ionesco traba relación estrecha con los cuadros de la Legión del Arcángel San Miguel o Guardia de Hierro, formación política de extrema derecha y de ideología nacionalista, agrega sus actividades de escritor a sus responsabilidades universitarias regulares con el dictado de seminarios: “Sobre el problema del mal en la filosofía india”, “Sobre la Docta ignorancia de Nicolás de Cusa”, “Sobre el libro X de la Metafísica de Aristóteles”, “Las Upanishads y el budismo”, etc.; publica el libro Yoga. Ensayo sobre los orígenes de la mística india, con pie de imprenta París-Bucarest, por lo editores Paul Geuthner/Fundación Real Carol I y aparecen tres números de la revista de historia de las religiones con colaboradores internacionales y de muy buen nivel que dirige, Zalmoxis. En l940 es nombrado agregado cultural de la Embajada Real de Rumania en Londres y al año siguiente Consejero de la Embajada Real de Rumania en Lisboa, aquí reside hasta 1945, cuando concluida la segunda guerra europea, le sobreviene la condición de exiliado. Durante este período que estamos teniendo en cuenta de gran fecundidad intelectual y de estabilidad político-laboral, se da el acontecimiento que registra el autor en el II volumen de las Memorias, Las promesas del soltiscio:

«Nos detuvimos durante dos días en Berlín. Uno de los agregados de prensa, Goruneanu, me llevó hasta Dahlem, a la casa de Carl Schmitt. Éste acababa de concluir en ese tiempo su librito sobre la Tierra y el mar y quería hacerme algunas preguntas sobre Portugal y las civilizaciones marítimas. Le hablé de Camoens y en particular del simbolismo acuático –Goruneanu le había ofrecido el volumen segundo de Zalmoxis en donde habían aparecido las “Notas sobre el simbolismo acuático”-. En la perspectiva de Carl Schmitt, Moby Dick constituía la mayor creación del espíritu marítimo después de la Odisea. No parecía entusiasmado por Los Lusiadas, que había leído en una traducción alemana. Conversamos durante tres horas. Nos acompañó hasta el subterráneo y, mientras caminábamos, nos explicó por qué consideraba la aviación como un símbolo terrestre….».

El encuentro tuvo lugar en julio de 1942, según precisa Mac Linscott Rioketts en su extensa y bien documentada biografía de Eliade.

Ahora bien, Ernst Jünger, gran amigo de Schmitt, que por esas fechas era oficial del Ejército alemán, estaba en Berlín con permiso y fue llamado a París para hacerse cargo de sus obligaciones militares. El 12 de noviembre fue a visitar a Dahlem a su amigo Schmitt a modo de despedida, estando con él del 12 al 17. El 15 estaba Jünger en casa del amigo y escribe lo siguiente en su Diario:

«Lectura de la revista Zalmoxis, cuyo título procede de un Hércules escita citado por Heródoto. He leído dos ensayos de ella, uno dedicado a los ritos de la extracción y uso de la mandrágora y el otro trataba del Simbolismo acuático, y de las relaciones entre la luna, las mujeres y el mar. Ambos de Mircea Eliade, el director de la revista. C.S. me proporcionó informaciones detalladas sobre él y sobre su maestro René Guénon. Las relaciones etimológicas entre las conchas marinas y el órgano genital de la mujer son particularmente significativas, como se ve en la palabra latina conc[h]a y en la danesa Kudefisk, en donde kude tiene el mismo sentido que vulva.

La mentalidad que se dibuja en esta revista es muy prometedora; en lugar de una escritura lógica, se trata de una escritura figurada. Son estas las cosas que me hacen el efecto del caviar, de las huevas de peces, se siente la fecundidad en cada frase».

En vísperas de Navidad del mismo año Eliade recibió Tierra y mar de parte de Schmitt, y Goruneanu le informa que el número 3 de Zalmoxis que había enviado a Schmitt lo acompañaba a Jünger en su mochila. Y esta triple relación de personas, directa, en un caso, e indirecta en el otro – por medio de la revista Zalmoxis-, se repite en 1944 y posteriormente. El primer caso se concretó por un nuevo encuentro de Schmitt -quien consideraba a Guénon: “El hombre más interesante de su tiempo” según señala Eliade en Fragmentos de Diario- con éste en Lisboa. En la visita de 1942, conjetura Grottanelli, de acuerdo con los testimonios de una simpatía recíproca de ambos personajes sobre Guénon, conversarían sobre él posiblemente no sólo como maestro sino también como teórico de la Tradición. El segundo encuentro a que nos hemos referido de Jürgen y Eliade y que nos interesa menos en este trabajo, llevó a que un tiempo después Jünger y Eliade dirigieran la revista Antaios.

En vísperas de Navidad del mismo año Eliade recibió Tierra y mar de parte de Schmitt, y Goruneanu le informa que el número 3 de Zalmoxis que había enviado a Schmitt lo acompañaba a Jünger en su mochila. Y esta triple relación de personas, directa, en un caso, e indirecta en el otro – por medio de la revista Zalmoxis-, se repite en 1944 y posteriormente. El primer caso se concretó por un nuevo encuentro de Schmitt -quien consideraba a Guénon: “El hombre más interesante de su tiempo” según señala Eliade en Fragmentos de Diario- con éste en Lisboa. En la visita de 1942, conjetura Grottanelli, de acuerdo con los testimonios de una simpatía recíproca de ambos personajes sobre Guénon, conversarían sobre él posiblemente no sólo como maestro sino también como teórico de la Tradición. El segundo encuentro a que nos hemos referido de Jürgen y Eliade y que nos interesa menos en este trabajo, llevó a que un tiempo después Jünger y Eliade dirigieran la revista Antaios.

Pues bien, de la mutua admiración que Schmitt y Eliade confesaban a mediados del año 1942, en plena guerra europea, por Guénon, el caso de C. Schmitt es documentalmente más accesible y claro, puesto que éste en un notable y bien conocido libro de 1938, Der Leviathan in der Staatslehre des Thomas Hobbes. Sinn und Fehlschlag eines politisches Symbols (El Leviatán en la teoría del estado de Thomas Hobbes. Sentido y fracaso de un símbolo político), entendía la componente esotérica como central en su composición, ya que Hobbes, exaltado por él dos años antes como el “gran inventor de la época moderna”, aparecía ahora en una nueva dimensión como quien había utilizado por error un símbolo en su tesis de política, el del monstruo marino de ascendencia religioso-cultural judía, que lo superaba en sus intenciones y se le imponía por su misma fuerza simbólica interna, poniéndolo bajo su control y manejándolo como un aprendiz de brujo. Y ahí mismo en el libro, en la nota 28, Schmitt recordaba a René Guénon, quien en la Crisis del mundo moderno de 1927, afirmaba la noción paralela y clave para la interpretación simbólica de que: «La rapidez con la que toda la civilización medieval sucumbió al ataque del siglo XVII es inconcebible sin la hipótesis de una misteriosa voluntad directriz que queda en la sombra y de una idea preconcebida». La ambivalencia del símbolo que tanto señala a la permanencia oculta de la Tradición como a los ataques aparentemente invisibles que asimismo recibe de la antitradicón y de la contratradición, y que puede aplicarse como un modo de justificación de la teoría política del complot o la conjuración político-social basada en la metafísica de la historia, es lo que le interesaba hacer notar a Schmitt, quien había sufrido dos años antes siendo Presidente de la Asociación de Juristas Alemanes y Consejero de Estado un ataque contra él en la revista de los SS Das Schwarze Korps, viéndose obligado a renunciar a todas sus funciones públicas. El empleo de la capacidad velada del símbolo para mostrar y ocultar por su poder esotérico de comunicación, es lo que veía Schmitt en Leviatán, serpiente marina guardiana del tesoro a veces para la enseñanza semítica y en otros momentos monstruo destructivo que proviene del mar, en el caso concreto aplicado su dimensión oscura y demoledora a la civilización cristiana y occidental más que milenaria. En este sentido igualmente el personaje que el libro encubría como destructor era Himmler y no Hitler.

Pero resultaba que si en este momento el libro de Guénon citado es La crisis del mundo moderno, Schmitt conocía mucho más del autor francés lo que explica el entusiasmo por él, según registra Eliade, pues en correspondencia entrecruzada unos años después con Armin Moler quien prepara su tesis sobre el jurista, al que le envía una carta el 19 de octubre de 1948 y que es respondida por Schmitt el 4 de diciembre. En las cartas cruzadas tenemos los siguientes datos:

«A la noche, después de haber trabajado en la tesis, siempre leo sus escritos, incluso los que aún no conozco. Os lo he referido ya que después de la visita que le hecho en Plettemberg, todo me parece más claro, con la sola excepción del Leviatán. Esta obra me sigue desorientando, y no sólo allí en donde, como al final del segundo capítulo, se hace alusión a un tema absolutamente nuevo [...]. La aparición de Guénon me ha sorprendido. ¿Conoce usted los escritos de este hombre singular? Siegfried Lang, uno de nuestros poetas más inspirados, me ha introducido hace algún tiempo en el estudio de su pensamiento».

Y esta es la contestación de C. Schmitt:

«Respecto del Leviatán, ya le he dicho que se trata de una obra totalmente esotérica; recuerde la “nota del autor” y las consideraciones del final del Prefacio, incluso si se trata de fórmulas evasivas. He leído mucho de Guénon, pero no la totalidad [de lo que ha escrito], lamentablemente. Nunca le he encontrado personalmente, pero he conocido a dos de sus amigos. Os interesará saber que el barón Julius Evola ha sido uno de sus fieles discípulos, pero no sé si Guénon vive todavía; según las últimas noticias que he recibido, pero que son de algunos años, vivía en el Cairo, con amigos musulmanes» (ver Grottanelli, 739).

Se advierte, por lo tanto, más allá del respeto intelectual y estimulante para la comprensión de los hechos histórico-políticos que Guénon inspiraba al jurista y filósofo político alemán, el uso aplicado que hacia del esoterismo, basado en el esoterismo riguroso de Guénon y Evola.

Está llegando el momento de dejar a C. Schmitt, porque estas jornadas están más centradas en Eliade y Guénon, pero para terminar con él, en confirmación de lo dicho vienen otras manifestaciones del autor, que la traducción española de la Ed. Trotta de Tierra y Mar ha incluido en una “Nota Final” debida a Franco Volpi. En ella se escribe, por medio de Nicolás Sombart, el hijo del famoso sociólogo e historiador de la economía, en referencia a Schmitt, que él se auto percibía como el guardián de un misterio, como un “iniciado”, al punto de que arcanum era una de las palabras que más repetía. Así Sombart cuenta esta anécdota en su relación con C. Schmitt, que:

«Un día [el mismo] Nicolaus preparaba una ponencia sobre la crítica teatral hebrea… Y consultado el profesor Schmitt, éste le repuso, no sabes en dónde te estás metiendo ¿Conoces la cuestión judía de C. Marx?, ¿Y a Disraeli?: Ni siquiera conoces a Disraeli y pretendes ocuparte de los judíos…Así puso en sus manos su novela Tancredo o la nueva cruzada, final de la trilogía que Benjamín Disraeli había publicado en 1847. Allí el gran político inglés, como buen esotérico, había encerrado en una obra literaria sus convicciones políticas más profundas. De este modo, en un pasaje borrado en la segunda edición de Tierra y mar lo llama Schmitt: “un iniciado, un sabio de Sión” y en Dahlen no tenía el jurista colgado un retrato de Hitler, sino de Disraeli. Y Schmitt asimismo le apunta a Nicolaus cual es la frase decisiva del libro, la que dice que: “El cristianismo es judaísmo para el pueblo”. Es la frase que da vuelta a dos mil años de historia. El conflicto entre judaísmo y catolicismo sobre la interpretación del sentido de la historia obsesionaba a Schmitt y la Modernidad era el campo de batalla del enfrentamiento…Los grandes pensadores hebreos del siglo XIX habían entendido que para llegar a la victoria en el plano de la historia universal necesitaban romper con el antiguo orden cristiano del mundo y acelerar la secularización y la disgregación de ese orden. El más temible teórico habría sido Disraeli, pues según su frase el cristianismo sería la estrategia urdida por los judíos para conquistar el sentido de la historia universal…La escatología estaba a punto de imponerse sobre el mesianismo…un orden universal en el que la “Nueva Jerusalén” colocada en el más acá es buscada por la élite judía…La Revolución Francesa aceleró el camino y la visión judía de dominio universal y la potencia marítima inglesa se fundieron en una simbiosis como un inmenso proyecto para la humanidad…El concepto de “retención” (katékhon) del cristianismo es ineficaz para poder guiar a la humanidad. Todo ello, remarca Schmitt, porque los judíos manejan el arte secreto de tratar con el Leviatán, saben domesticarlo para en el momento oportuno descuartizarlo. Era necesario descubrir las técnicas ocultas para penetrar en los arcana imperii y salir sin daños definitivos de la lucha, una lucha por el simbolismo y su tradición, frente a los intentos destructivos de sus dominadores profanos e inmanentes».

Resulta transparente que de esta convicción y familiaridad con los diversos niveles de sentido del símbolo y del contacto con el fondo subyacente que circula ocultamente en el tiempo histórico, había extraído Schmitt confianza y serenidad para profundizar la comprensión teórica y sobrellevar la existencia práctica. Así lo demostró al haber aceptado voluntariamente ser juzgado por el Tribunal de Núremberg, denunciado por un ex colega de la Universidad de Berlín docente ahora en una universidad estadounidense, Karl Loewenstein y legal adviser del Jurado. La defensa personal que llevó a cabo Schmitt le exige trazar una sutil, pero precisa frontera, entre su pensamiento y la ideología nacionalsocialista y de este modo afirma que de ninguna manera podría haber influido en la política de los grandes espacios del III Reich, ni a preparar la guerra de agresión con sus consecuencias criminales, ni a gravitar en cualquier tipo de decisiones de los funcionarios de alto rango. Por ejemplo, defendió que su concepto de Grossraum (gran espacio) se basaba en el derecho internacional y no en el sentido nacionalista que le dio el régimen. A la categoría moderna de estado, válida desde Hobbes a Hegel, él contrapone la de “gran espacio”, que no es simplemente “espacio terrestre”, sino también “espacio imperial”. Aquí es en donde se juega el nuevo ordenamiento político-jurídico del planeta. Esta categoría no depende de la concepción biológico-racista del “espacio vital” (Lebensraum) ni de la categoría nacionalista (völkisch) nacionalsocialistas, para entender su concepción del “gran espacio”; sino que mejor, este último concepto se aproxima más a la doctrina Monroe norteamericana del principio de no injerencia de una potencia extranjera en un gran espacio terrestre ajeno, organizado según un orden jurídico-político propio. Un gran espacio imperial se forma cuando un estado desarrolla una potencia que excede sus propios límites y tiende a agregar en torno a sí a otros estados y es esta conveniencia de formar grandes bloques continentales la que puede generar un nuevo escenario de organización internacional, rompiendo la impotencia de las Naciones Unidas de Ginebra y conteniendo el ascenso de una superpotencia individual. Justamente el pequeño libro Tierra y mar si de entrada parecía aportarle complicaciones, explicado en su doctrina, le trajo la definitiva absolución en mayo de 1947, con curiosos diálogos durante el interrogatorio como el siguiente: «”En aquel tiempo me sentía superior. Quería dar un sentido propio a la palabra nacionalsocialismo”. “Por tanto, ¿Hitler tenía un nacionalsocialismo y usted otro distinto?”. “Yo me sentía superior”. “¿Superior a Hitler?” “Desde el punto de vista intelectual, infinitamente”.

Mircea Eliade, sin embargo, más joven y perteneciente a un país de cultura minoritaria, Rumania, si bien padeció el exilio y los severos obstáculos de un intelectual emigrado en París, no tuvo que enfrentarse con tan grandes dificultades. Las bases guenonianas de la organización de sus ideas, aunque menos conocidas por estar escritas en rumano y hechas conocer en publicaciones locales y muy poco difundidas, igualmente están registradas. Escribe así por primera vez M. Eliade en la revista Azi en abril de 1932, refiriéndose a Guénon, en una cita que se refiere al Teosofismo: historia de una falsa religión:

«Remito al lector al libro de Guénon, quien es un ocultista muy importante y muy bien informado, con una mentalidad sólida y que, al menos, sabe de lo que habla [a diferencia de Elena Blavatsky]» (Grottanelli, p. 346).

En 1937 escribe un artículo sobre Ananda Coomaraswamy en la Revista Fundaitilior Regale, republicado en 1943, y allí expresa que «es de lamentar que los escritos de Guénon, como Oriente y Occidente (1924) y La crisis del mundo moderno (1927), no hayan tenido sino una difusión limitada, ya que ellos mostraban que el tradicionalismo religioso no tenía nada que temer en Europa a la influencia de la metafísica oriental, contrariamente a lo que pensaban algunos escritores católicos» (Grottanelli, 346). Es razonable deducir, sin embargo, pese a las lamentaciones de Eliade y si se piensa en Schmitt y Evola, que el libro de Guénon La crisis del mundo moderno había tenido al menos repercusión propia en la derecha europea, como también lo tuvo en la Argentina, como hemos dicho, poco después de ser publicado.

En otro artículo aparecido en Vremea el l° de mayo de 1938, nuevamente Eliade se queja de la falta de difusión de la obra de Guénon y que sea tan poco conocida como la de Evola y Coomaraswamy . Hace igualmente aquí un curioso elogio de la personalidad de René Guénon como testigo de la tradición, «que era capaz de mostrar un desprecio absoluto y olímpico por el mundo moderno en su conjunto. Un menosprecio sin cólera, sin irritación y sin melancolía. Un desdén que alejaba a este pensador de los hombres de su tiempo y de su obsesión por la historia. Una actitud heroica, comparable, aunque preferible, a aquella de que hablaba André Malraux en su libro Le temps du mépris, que era el tema del ensayo de Eliade” (Grottanelli, 347).

Eliade en estos tiempos en los inicios de sus treinta años, cuando está forjando su personalidad de teórico e investigador considera a Guénon como un auténtico maestro en el campo de las ideas tradicionales, lo que incluso ratifica a su juicio la serena posición de desapego ante las corrientes de ideas modernas, aunque no emite el mismo juicio favorable en el campo de la investigación, como también lo ha expresado en el artículo dedicado a Coomaraswamy. A éste sí lo considera lingüística y filológicamente competente, mientras que para Guénon y Evola, en este campo, se le escapa la baja calificación de “dilettantes”. La evaluación en este último caso de M. Eliade es compleja, porque incluye aproximación y simpatía respecto de las ideas de fondo, pero alejamiento en el método de llegar a ellas, un fenómeno que vamos enseguida a comentar, pero antes debemos facilitar también otra ratificación que es de la misma época, y que se contiene en el libro Comentarii la legenda Mesterului Manole, que se refiere a las leyendas rumanas y balcánicas de los sacrificios de niños durante la construcción de edificios, en particular de monasterios y de puentes, que es publicado en Lisboa siete años después, en marzo de 1943, y en donde el autor confirma en el prefacio:

«Esta obra se publica con una demora de al menos seis años. En uno de los cursos de historia y de filosofía de las religiones que habíamos profesado en la Facultad de Letras de Bucarest (1936-1937, en reemplazo del curso de metafísica del Prof. Nae Ionescu), tuvimos la oportunidad de exponer en sus grandes líneas, el contenido y los resultados de este libro. Una versión técnica de estas lecciones, provista de todo el aparato científico necesario, se preparó hace ya bastante tiempo – bajo el título de Manole et les rites de cosntruction – para la revista Zalmoxis. Pero las circunstancias, y sobre todo la larga residencia del editor en el extranjero, han impedido la aparición regular de Zalmoxis, de modo que antes de publicar la versión técnica, hemos considerado que no estaría desprovisto de interés publicar los presentes Comentarios». Y prosigue el prólogo aportando esclarecimientos críticos y justificativos del mayor interés:

«Evidentemente es indispensable reunir, clasificar e interpretar los documentos etnográficos, pero esto no puede revelar mucho sobre la espiritualidad arcaica. Es necesario ante todo un conocimiento satisfactorio de la historia de las religiones y de la teoría metafísica implícita en los ritos, los símbolos, las cosmogonías y los mitos. La mayor parte de la bibliografía internacional que trata del folclore y de la etnografía es valiosa en la medida en que presenta el material auténtico de la espiritualidad popular, pero deja mucho que desear cuando trata de explicar este material, por medio de “leyes” al uso, a la moda del tiempo de Taylor, Mannhardt o Frazer. No es este el lugar de entablar un examen crítico de los diferentes métodos de interpretación de los documentos de la espiritualidad arcaica. Cada uno de estos métodos ha tenido, en su tiempo, determinados méritos. Pero casi todos se han ajustado a la historia (correcta o incorrectamente comprendida) de este o aquel documento folclórico o etnográfico, con preferencia a tratar de descubrir el sentido espiritual que ha tenido y restaurar su consistencia íntima. La reacción contra estos métodos positivistas no ha tardado en hacerse sentir y es especialmente expresada por un Olivier Leroy, entre los etnólogos, por un René Guénon y un Julius Evola, entre los filósofos, por un Ananda Coomaraswamy entre los arqueólogos, etcétera. Ella ha ido tan lejos que a veces ha negado la evidencia de la historia e ignorado en su totalidad los hechos recogidos por los investigadores» (Grottanelli, 350-351).

Nuevamente en este texto transparente están reunidas por Eliade las dos puntas de su posición de aceptación y crítica en relación con Guénon y otros autores vecinos por las ideas: simbolismo e ideas tradicionales garantizadores de la universalidad de las creencias sagradas como fondo organizador, pero a partir de la investigación científica. El reunir y avecinar documentos no es erudición positivista ni vacía, sino que en el allegamiento surgen ante la mente sensible y perspicaz a los fenómenos aproximadamente las ideas y principios transcendentes que subyacen. Las hierofanías, como manifestaciones de lo sagrado, revelan uniones o integraciones mediadoras que ligan a los contrarios –lo profano y lo sagrado- con equilibrio, lo organizan en sistemas estructurales en el lenguaje del símbolo y del mito, y permiten al alma religiosa arcaica y actual ascender a los orígenes constitutivos. No hay una diferencia insalvable acerca del reconocimiento del fondo espiritual entre Eliade y Guénon, sí lo hay en cuanto al método de acceso. Firmeza de la tradición y de la iniciación en cuanto a Guénon, ingreso por el reconocimiento de los fenómenos sagrados reflejados en la conciencia que cada vez exigen mayor comprensión, para Mircea Eliade. Guénon aspira a romper con lo profano para tener acceso no reflejo, sino directo a lo sagrado; Eliade, se sumerge en la dialéctica de lo sagrado y lo profano que acompaña a la vida del cosmos y la sociedad. Lo primero da una existencia digna de iniciados; lo segundo, de hombres en el mundo vitalmente sacro, que eligen diferentes destinos.

Nuevamente en este texto transparente están reunidas por Eliade las dos puntas de su posición de aceptación y crítica en relación con Guénon y otros autores vecinos por las ideas: simbolismo e ideas tradicionales garantizadores de la universalidad de las creencias sagradas como fondo organizador, pero a partir de la investigación científica. El reunir y avecinar documentos no es erudición positivista ni vacía, sino que en el allegamiento surgen ante la mente sensible y perspicaz a los fenómenos aproximadamente las ideas y principios transcendentes que subyacen. Las hierofanías, como manifestaciones de lo sagrado, revelan uniones o integraciones mediadoras que ligan a los contrarios –lo profano y lo sagrado- con equilibrio, lo organizan en sistemas estructurales en el lenguaje del símbolo y del mito, y permiten al alma religiosa arcaica y actual ascender a los orígenes constitutivos. No hay una diferencia insalvable acerca del reconocimiento del fondo espiritual entre Eliade y Guénon, sí lo hay en cuanto al método de acceso. Firmeza de la tradición y de la iniciación en cuanto a Guénon, ingreso por el reconocimiento de los fenómenos sagrados reflejados en la conciencia que cada vez exigen mayor comprensión, para Mircea Eliade. Guénon aspira a romper con lo profano para tener acceso no reflejo, sino directo a lo sagrado; Eliade, se sumerge en la dialéctica de lo sagrado y lo profano que acompaña a la vida del cosmos y la sociedad. Lo primero da una existencia digna de iniciados; lo segundo, de hombres en el mundo vitalmente sacro, que eligen diferentes destinos.

Esta diferencia de posiciones explica las relaciones entre ambos autores, que parecen incluir fuertes contrastes. Guénon desde 1940 en adelante comenta libros y artículos de Mircea Eliade en la revista Études Traditionelle, reconociendo sus aciertos de exposición e interpretación por momentos, así como desautorizándole agriamente en otras, abrogándose la postura de señor indiscutido del campo tradicional que le compete (Técnicas del Yoga, el tomo II de Zalmoxis, «Le “dieu lieur” et le symbolisme des noeuds» -RHR y referencia positiva en “Ligaduras y nudos”É.T., marzo 1950-, Le mythe de l’éternel retour, y otros escritos incluidos en Compte Rendus), una especie de rictus del tradicionalista francés que también ha dado origen a lo que podemos considerar lo más alejado de su magisterio, la “ideología guenoniana”. Mircea Eliade, por su parte, cuando comienza a publicar su difundida obra de especialista en Historia de la religiones a partir del Tratado de historia de las religiones que le publica Payot en l947, en donde recoge materiales anteriormente redactados y otros nuevos, apenas tiene en cuenta en la bibliografía del último capítulo sobre “La estructura de los símbolos”, un escrito de Guénon, Le symbolisme de la croix. Ni siquiera aparece el magisterio expressis verbis del maestro Guénon en los capítulos V (“Las aguas y el simbolismo acuático”) del Tratado y el IV de Imágenes y símbolos (1955), que reedita el primitivo artículo del número 2 de Zalmoxis que tanto le había interesado a Ernst Jünger. Sin embargo, en Le Voile d’Isis (Octubre de 1931) hay un artículo sobre Shet con una referencia a Behemot -en plural- del Libro de Job, como una designación general para todos los grandes cuadrúpedos, lo que es ampliado en el número de agosto-septiembre de 1938 en Études Traditionnelle en una colaboración sobre “Los misterios de la letra nun” (ambos artículos están recogidos más tarde por Michel Valsan –otro rumano- en Símbolos fundamentales de la ciencia sagrada) en donde Guénon se refiere al aspecto benéfico y maléfico de la ballena, con su doble significado de muerte y resurrección, y su vinculación con el Leviatán hebreo y Behemot, como “los hijos de la ballena”. Este trabajo está dentro de la línea de símbolos desarrollados por C. Schmitt en Tierra y mar –Behemot, Leviatán, Grifo- y puede haber sido conocido por el autor alemán.

Mircea Eliade, sin embargo, en su fecunda y subsiguiente producción hace silencio sobre Guénon. Recién en escritos de la década del setenta, el artículo que hemos citado antes sobre la “Theosophia oculta” se refiere a él con elogios y en Ocultismo, brujería y modas culturales, publicado por la Universidad de Chicago en la segunda mitad de los 70, le dedica dos referencias elogiosas a su postura intransigente y bien fundada frente al ocultismo acrítico y optimista de la segunda mitad del siglo XX y algo más de tres páginas para presentarlo como el renovador del esoterismo contemporáneo. Por otra parte, su interpretación de la doctrina cíclica del autor como pesimista y catastrófica en esas páginas demuestra no haber comprendido la concepción guenoniana de los ciclos cósmicos fundada en el Vedânta no dualista de Shankara que incluye ciclos internos espiralados contenidos en el ciclo mayor de un kalpa o “día de Brahman”, con sus manvantaras y yugas, identificando esta visión hindú con la mítico-greca de los pueblos arcaicos, una ligereza de interpretación que el mismo Guénon le había reprochado en la reseña que le dedicó al Mito del eterno retorno. Los silencios y lagunas de comprensión de Eliade sobre R. Guénon, al que reconocía como maestro y orientador en su juventud son sospechosos y el haberlo acantonado a ser “el representante más prominente del esoterismo moderno” sin rastros de su influencia docente sobre él mismo, tal vez despunte una solución en la opinión enseguida proferida en el escrito al que nos estamos refiriendo: «Durante su vida Guénon fue más bien un autor impopular. Tuvo admiradores fanáticos, pero muy pocos. Sólo después de su muerte, y en especial en los diez o doce años últimos, sus libros fueron reeditados y traducidos, difundiendo ampliamente sus ideas» (p. 107).

Casi contemporáneamente en los diálogos sostenidos con Claude-Henri Rocquet y que se han publicado en español bajo el título de La prueba del laberinto (1980) respondiendo a una pregunta del entrevistador, torna a hacer Eliade declaraciones sobre Guénon, pero en este caso resultan incluso más desconcertantes para el lector, por ser contradictorias con lo que hasta ahora se ha podido demostrar. Porque afirma primero el estudioso rumano: «Leí a René Guénon muy tarde y algunos de sus libros me han interesado mucho, concretamente L’Homme et son devenir selon le Vedanta, que me ha parecido bellísimo, inteligente y profundo». A continuación vienen expresadas algunas reservas del autor acerca de lo que no le agrada del escritor francés: su lado exageradamente polémico, un cierto tic de superioridad y un balance de repulsa de toda la cultura occidental -incluida la universitaria- y el respaldo persistente en un concepto complejo y carente de univocidad como es el que pretende sostener sobre la tradición. Este último análisis es bastante discutible, porque Eliade no demuestra poder facilitar un concepto rigurosamente diáfano de tradición, pero sobre todo, creemos que hay que llamar la atención sobre la aclaración de que «leyó a René Guénon muy tarde», puesto que los datos recopilados de su historia de juventud confirman lo contrario. Parece ser que el libro que era el estandarte de la cruzada en la que participaba con otros jóvenes intelectuales en los años treinta en Bucarest, La crisis del mundo moderno, era un obstáculo difícil de salvar para un exitoso profesor que se movía con facilidad en el ambiente universitario estadounidense.

Conclusiones sobre René Guénon y su influencia sobre Eliade y Schmitt.

La atmósfera cultural de la posguerra en París en la que un estudioso rumano de las religiones próximo a los cuarenta años o ya entrados en ellos, hubo de abrirse camino en la Sorbona y los círculos de investigación que la rodeaban, debieron gravitar pesadamente sobre el refugiado político Mircea Eliade. Se sabe de los problemas que tuvo Guénon para que le fuera admitida como tesis universitaria la Introducción general a las doctrinas hindúes, la que finalmente le fue rechazada, y su reacción de abandono del medio universitario. Si el refugiado Eliade, no obstante el apoyo que le prodigaron especialistas franceses como H.Ch. Puech, G. Dumézil, M. Masson-Oursel, L. Renou y otros, tuvo muy serias dificultades para insertarse en el entorno universitario parisino e incluso que en ciertos momentos las dificultades provinieron de la presión política con que lo asediaba el aparato de la inteligencia policial de su país de origen, el silenciar los contactos doctrinales con Guénon cuando era integrante de la Guardia de Hierro durante parte de los años 30 y los primeros del cuarenta, miembro activo de sus avatares políticos y publicaba en sus órganos de prensa y, además, la previsión de no irritar a sus benefactores parisinos inmediatos rompiendo “la conspiración del silencio” que pesaba sobre Guénon en los grupos universitarios oficiales franceses, era cuestión de vida o muerte en aquella etapa para la existencia académica y de investigación del notable universitario que llegó a ser el exiliado rumano. Posteriormente insertado sólidamente en el contexto de la vida universitaria de occidente, el prejuicio lo persiguió como un fantasma. En el fondo, del entramado teórico de sus trabajos quedaba, sin embargo, la influencia teórica subyacente con la que gracias al estímulo doctrinal de Guénon organizó sus aspiraciones de transcendencia al definir la naturaleza religiosa, simbólica y mítica del hombre arcaico y de su desarrollo cósmico.

El caso de Carl Schmitt, sin embargo, fue diverso y transparente, puesto que cuando tiene casi concluido Tierra y mar y está obsesionado por su contenido y recibe a un joven funcionario de Embajada rumano -el que había llevado un mensaje privado a Antunesco, el hombre fuerte del régimen militar de Bucarest del par portugués Salazar-, tiene 54 años. Alemania está en plena guerra europea y el jurista prestigioso se encuentra enfrentado con parte del entorno nacionalsocialista. Las lecturas que había realizado de Guénon estimulaban sus creencias católicas firmes y le permitían utilizar el simbolismo para la interpretación transcendente y velada de los acontecimientos histórico-políticos. Ningún riesgo de fondo corría, al contrario, con este tipo de incursiones culturales profundas, según su mejor inclinación, le era posible ampliar su figura de gran jurista del derecho internacional y afirmarse como filósofo e intérprete político-jurídico del difícil momento del proceso bélico alemán.

El tiempo transcurrido desde entonces hasta hoy parece darnos la razón. Y al ver confluir las tres poderosas personalidades sobre un mismo tema, el de la interpretación de los fenómenos visibles y próximos de la religión, la política y la historia, permite dar asimismo una pincelada de profundidad a lo que hoy día se está mostrando incontrolable y difícil de silenciar en la esfera de la política práctica y de la teoría política: que no es posible pensar en los hechos actuales si no nos liberamos de ellos elevándonos al plano de la metapolítica, bien sea desde la teología o desde la metafísica. La teología política de Jacobo Taubes y de Jian Assmann así lo están reclamando en los centros de estudio internacionales, pero las dos figuras que hemos tratado inspiradas por René Guénon, confirman que la necesidad de implantar el llamado “modelo dualista”, que no es ni simplemente teocrático ni representativo individualista, ofrece matices y recursos para que el ciudadano de los comienzos del siglo XXI se ponga a pensar seriamente que la marcha de los pueblos y sus ordenamientos políticos, jurídicos y económicos son inseparables de algún modo de trascendencia sagrada y tradicional.

Bibliografía

C. Bori, «Théologie politique et Islam. À propos d’Ibn Taymiyya (m. 728/1328) et du sultanat mamelouk», en RHR, 224 (207), 1, 5-46.

A. Désilets, René Guénon. Index-Bibliographie, Les Presses de L’Université Laval, Québec, 1977.

P. Di Vona, «René Guénon e il pensiero di destra», en La destra como categoria, Hermeneutica, Istituto di Scienze Religiose dell’Università degli Studi di Urbino, 1988, 59-85.

M. Eliade, Tratado de historia de las religiones, Inst. de Est. Políticos, Madrid, 1954.

M. Eliade, Imágenes y símbolos. Ensayos sobre el simbolismo mágico-religioso, Taurus, Madrid, 1955.

M. Eliade, «El ocultismo y el mundo moderno», en Ocultismo, brujería y modas culturales, Marymar, Buenos Aires, 1977, 79-108.

M. Eliade, La prueba del laberinto, Cristiandad, Madrid, 1980.

M. Eliade, Memoria I. 1907-1937. Las promesas del equinoccio, Taurus, Madrid, 1982.

M. Eliade, De Zalmoxis a Gengis-Khan. Religiones y folklore de Dacia y de la Europa Oriental, Cristiandad, Madrid, 1985.

M. Eliade, Diario. 1945-1969, Kairós, Barcelona, 2000.

F. García Bazán y otros, René Guénon o la tradición viviente, Hastinapura, Buenos Aires, 1985.

F. García Bazán, René Guénon y el ocaso de la metafísica, Obelisco, Barcelona, 1990.

C. Grottanelli, «Mircea Eliade, Carl Schmitt, René Guénon, 1942», en Revue de l’Histoire des Religions, tome 219, 3 (2002), 325-356.

J.-P. Laurant, «Guénon, René», en J. Servier (dir.), Diccionario AKAL crítico de esoterismo, 2 vols., Akal, Madrid, 2006, A-H, 753-756.

T.M.P. Mahadevan, Guadapâda. A Study in Early Advaita, University of Madras, 1975.

C. Schmitt, Tierra y mar. Una reflexión sobre la historia universal con un prólogo de Ramón Campderrich y un epílogo de Franco Volpi, Trotta, Madrid, 2007.

J. Taubes, La teología política de Pablo, Trotta, Madrid, 2007

Fuente: Centro de Estudios Evoliano

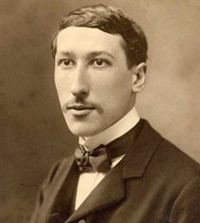

On January 7th, 1951, the Frenchman René Guénon, one of the principal representatives of Traditional thought in the 20th century, died in Cairo.

On January 7th, 1951, the Frenchman René Guénon, one of the principal representatives of Traditional thought in the 20th century, died in Cairo.

Le penseur français René Guénon (1886 – 1957) ne suscite que très rarement l’intérêt de l’université hexagonale. On doit par conséquent se réjouir de la sortie de René Guénon. Une politique de l’esprit par David Bisson. À l’origine travail universitaire, cet ouvrage a été entièrement retravaillé par l’auteur pour des raisons d’attraction éditoriale évidente. C’est une belle réussite aidée par une prose limpide et captivante.

Le penseur français René Guénon (1886 – 1957) ne suscite que très rarement l’intérêt de l’université hexagonale. On doit par conséquent se réjouir de la sortie de René Guénon. Une politique de l’esprit par David Bisson. À l’origine travail universitaire, cet ouvrage a été entièrement retravaillé par l’auteur pour des raisons d’attraction éditoriale évidente. C’est une belle réussite aidée par une prose limpide et captivante. Au cours de l’Entre-deux-guerres, le futur historien des religions affine sa propre vision du monde. Alimentant sa réflexion d’une immense curiosité pluridisciplinaire, il a lu – impressionné – les écrits de Guénon. D’abord rétif à tout militantisme politique, Eliade se résout sous la pression de ses amis et de son épouse à participer au mouvement politico-mystique de Corneliu Codreanu. Il y devient alors une des principales figures intellectuelles et y rencontre un nommé Cioran. Au sein de cet ordre politico-mystique, Eliade propose un « nationalisme archaïque (p. 252) » qui assigne à la Roumanie une vocation exceptionnelle. Son engagement dans la Garde de Fer ne l’empêche pas de mener une carrière de diplomate qui se déroule en Grande-Bretagne, au Portugal et en Allemagne. Son attrait pour les « mentalités primitives » et les sociétés traditionnelles pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale s’accroît si bien qu’exilé en France après 1945, il jette les premières bases de l’histoire des religions qui le feront bientôt devenir l’universitaire célèbre de Chicago. Si Eliade s’éloigne de Guénon et ne le cite jamais, David Bisson signale cependant qu’il lui expédie ses premiers ouvrages. En retour, ils font l’objet de comptes-rendus précis. Bisson peint finalement le portrait d’un Mircea Eliade louvoyant, désireux de faire connaître et de pérenniser son œuvre.

Au cours de l’Entre-deux-guerres, le futur historien des religions affine sa propre vision du monde. Alimentant sa réflexion d’une immense curiosité pluridisciplinaire, il a lu – impressionné – les écrits de Guénon. D’abord rétif à tout militantisme politique, Eliade se résout sous la pression de ses amis et de son épouse à participer au mouvement politico-mystique de Corneliu Codreanu. Il y devient alors une des principales figures intellectuelles et y rencontre un nommé Cioran. Au sein de cet ordre politico-mystique, Eliade propose un « nationalisme archaïque (p. 252) » qui assigne à la Roumanie une vocation exceptionnelle. Son engagement dans la Garde de Fer ne l’empêche pas de mener une carrière de diplomate qui se déroule en Grande-Bretagne, au Portugal et en Allemagne. Son attrait pour les « mentalités primitives » et les sociétés traditionnelles pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale s’accroît si bien qu’exilé en France après 1945, il jette les premières bases de l’histoire des religions qui le feront bientôt devenir l’universitaire célèbre de Chicago. Si Eliade s’éloigne de Guénon et ne le cite jamais, David Bisson signale cependant qu’il lui expédie ses premiers ouvrages. En retour, ils font l’objet de comptes-rendus précis. Bisson peint finalement le portrait d’un Mircea Eliade louvoyant, désireux de faire connaître et de pérenniser son œuvre. En étroite correspondance épistolaire avec Guénon, Schuon devient son « fils spirituel ». cela lui permet de recruter de nouveaux membres pour sa confrérie soufie qu’il développe en Europe. D’abord favorable à son islamisation, Schuon devient ensuite plus nuancé, « la forme islamique ne contrevenant, en aucune manière, à la dimension chrétienne de l’Europe. Il essaiera même de fondre les deux perspectives dans une approche universaliste dont l’ésotérisme sera le vecteur (p. 172) ». Cette démarche syncrétiste s’appuie dès l’origine sur son nom musulman signifiant « Jésus, Lumière de la Tradition».

En étroite correspondance épistolaire avec Guénon, Schuon devient son « fils spirituel ». cela lui permet de recruter de nouveaux membres pour sa confrérie soufie qu’il développe en Europe. D’abord favorable à son islamisation, Schuon devient ensuite plus nuancé, « la forme islamique ne contrevenant, en aucune manière, à la dimension chrétienne de l’Europe. Il essaiera même de fondre les deux perspectives dans une approche universaliste dont l’ésotérisme sera le vecteur (p. 172) ». Cette démarche syncrétiste s’appuie dès l’origine sur son nom musulman signifiant « Jésus, Lumière de la Tradition». Mais qu’est-ce que la multipolarité ? Pour Alexandre Douguine, ce phénomène « procède d’un constat : l’inégalité fondamentale entre les États-nations dans le monde moderne, que chacun peut observer empiriquement. En outre, structurellement, cette inégalité est telle que les puissances de deuxième ou de troisième rang ne sont pas en mesure de défendre leur souveraineté face à un défi de la puissance hégémonique, quelle que soit l’alliance de circonstance que l’on envisage. Ce qui signifie que cette souveraineté est aujourd’hui une fiction juridique (pp. 8 – 9) ». « La multipolarité sous-tend seulement l’affirmation que, dans le processus actuel de mondialisation, le centre incontesté, le noyau du monde moderne (les États-Unis, l’Europe et plus largement le monde occidental) est confronté à de nouveaux concurrents, certains pouvant être prospères voire émerger comme puissances régionales et blocs de pouvoir. On pourrait définir ces derniers comme des “ puissances de second rang ”. En comparant les potentiels respectifs des États-Unis et de l’Europe, d’une part, et ceux des nouvelles puissances montantes (la Chine, l’Inde, la Russie, l’Amérique latine, etc.), d’autre part, de plus en plus nombreux sont ceux qui sont convaincus que la supériorité traditionnelle de l’Occident est toute relative, et qu’il y a lieu de s’interroger sur la logique des processus qui déterminent l’architecture globale des forces à l’échelle planétaire – politique, économie, énergie, démographie, culture, etc. (p. 5) ». Elle « implique l’existence de centres de prise de décision à un niveau relativement élevé (sans toutefois en arriver au cas extrême d’un centre unique, comme c’est aujourd’hui le cas dans les conditions du monde unipolaire). Le système multipolaire postule également la préservation et le renforcement des particularités culturelles de chaque civilisation, ces dernières ne devant pas se dissoudre dans une multiplicité cosmopolite unique (p. 17) ». Le philosophe russe s’inspire de certaines thèses de l’universitaire réaliste étatsunien, Samuel Huntington. Tout en déplorant les visées atlantistes et occidentalistes, l’eurasiste russe salue l’« intuition de Huntington qui, en passant des États-nations aux civilisations, induit un changement qualitatif dans la définition de l’identité des acteurs du nouvel ordre mondial (p. 96) ».

Mais qu’est-ce que la multipolarité ? Pour Alexandre Douguine, ce phénomène « procède d’un constat : l’inégalité fondamentale entre les États-nations dans le monde moderne, que chacun peut observer empiriquement. En outre, structurellement, cette inégalité est telle que les puissances de deuxième ou de troisième rang ne sont pas en mesure de défendre leur souveraineté face à un défi de la puissance hégémonique, quelle que soit l’alliance de circonstance que l’on envisage. Ce qui signifie que cette souveraineté est aujourd’hui une fiction juridique (pp. 8 – 9) ». « La multipolarité sous-tend seulement l’affirmation que, dans le processus actuel de mondialisation, le centre incontesté, le noyau du monde moderne (les États-Unis, l’Europe et plus largement le monde occidental) est confronté à de nouveaux concurrents, certains pouvant être prospères voire émerger comme puissances régionales et blocs de pouvoir. On pourrait définir ces derniers comme des “ puissances de second rang ”. En comparant les potentiels respectifs des États-Unis et de l’Europe, d’une part, et ceux des nouvelles puissances montantes (la Chine, l’Inde, la Russie, l’Amérique latine, etc.), d’autre part, de plus en plus nombreux sont ceux qui sont convaincus que la supériorité traditionnelle de l’Occident est toute relative, et qu’il y a lieu de s’interroger sur la logique des processus qui déterminent l’architecture globale des forces à l’échelle planétaire – politique, économie, énergie, démographie, culture, etc. (p. 5) ». Elle « implique l’existence de centres de prise de décision à un niveau relativement élevé (sans toutefois en arriver au cas extrême d’un centre unique, comme c’est aujourd’hui le cas dans les conditions du monde unipolaire). Le système multipolaire postule également la préservation et le renforcement des particularités culturelles de chaque civilisation, ces dernières ne devant pas se dissoudre dans une multiplicité cosmopolite unique (p. 17) ». Le philosophe russe s’inspire de certaines thèses de l’universitaire réaliste étatsunien, Samuel Huntington. Tout en déplorant les visées atlantistes et occidentalistes, l’eurasiste russe salue l’« intuition de Huntington qui, en passant des États-nations aux civilisations, induit un changement qualitatif dans la définition de l’identité des acteurs du nouvel ordre mondial (p. 96) ». Piochant dans toutes les écoles théoriques existantes, le choix multipolaire de Douguine n’est au fond que l’application à un domaine particulier – la géopolitique – de ce qu’il nomme la « Quatrième théorie politique ». Titre d’un ouvrage essentiel, cette nouvelle pensée politique prend acte de la victoire de la première théorie politique, le libéralisme, sur la deuxième, le communisme, et la troisième, le fascisme au sens très large, y compris le national-socialisme.

Piochant dans toutes les écoles théoriques existantes, le choix multipolaire de Douguine n’est au fond que l’application à un domaine particulier – la géopolitique – de ce qu’il nomme la « Quatrième théorie politique ». Titre d’un ouvrage essentiel, cette nouvelle pensée politique prend acte de la victoire de la première théorie politique, le libéralisme, sur la deuxième, le communisme, et la troisième, le fascisme au sens très large, y compris le national-socialisme.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

René Guénon (1886 – 1951) est mal vu des milieux identitaires qui n’apprécient pas sa conversion à l’islam soufi dès 1911 sous le nom musulman d’Abd el-Wâhed Yahia, « Serviteur de l’Unique ». Quant aux milieux contre-révolutionnaires, outre ce tropisme oriental marqué, ils l’accusent d’être passé par la franc-maçonnerie et certains cénacles gnostiques. Or ces attaques bien trop réductrices éclipsent une œuvre intellectuelle majeure. « La pensée de Guénon constitue un chapitre original, et non négligeable, de l’histoire intellectuelle (p. 488). »

René Guénon (1886 – 1951) est mal vu des milieux identitaires qui n’apprécient pas sa conversion à l’islam soufi dès 1911 sous le nom musulman d’Abd el-Wâhed Yahia, « Serviteur de l’Unique ». Quant aux milieux contre-révolutionnaires, outre ce tropisme oriental marqué, ils l’accusent d’être passé par la franc-maçonnerie et certains cénacles gnostiques. Or ces attaques bien trop réductrices éclipsent une œuvre intellectuelle majeure. « La pensée de Guénon constitue un chapitre original, et non négligeable, de l’histoire intellectuelle (p. 488). » Dès les années 1930, René Guénon rencontre un élève talentueux en la personne de Frithjof Schuon. Converti à l’islam et devenu très tôt cheikh (chef spirituel) d’une tarîqa (communauté) soufie, Schuon entend régler la question de l’initiation des Européens par l’islam. Il déclare ainsi qu’« il faut islamiser l’Europe (p. 172) » avant de revenir à des dispositions plus nuancées. Après 1945, le musulman Schuon est devenu un fin connaisseur du christianisme. Il considère que les sacrements chrétiens font des chrétiens des initiés involontaires ou ignorants. Il vouera ensuite un culte particulier à la Vierge Marie et s’ouvrira au chamanisme amérindien. En 1981, Schuon s’installe aux États-Unis dans l’Indiana d’où il décédera dix-sept ans plus tard.

Dès les années 1930, René Guénon rencontre un élève talentueux en la personne de Frithjof Schuon. Converti à l’islam et devenu très tôt cheikh (chef spirituel) d’une tarîqa (communauté) soufie, Schuon entend régler la question de l’initiation des Européens par l’islam. Il déclare ainsi qu’« il faut islamiser l’Europe (p. 172) » avant de revenir à des dispositions plus nuancées. Après 1945, le musulman Schuon est devenu un fin connaisseur du christianisme. Il considère que les sacrements chrétiens font des chrétiens des initiés involontaires ou ignorants. Il vouera ensuite un culte particulier à la Vierge Marie et s’ouvrira au chamanisme amérindien. En 1981, Schuon s’installe aux États-Unis dans l’Indiana d’où il décédera dix-sept ans plus tard.

II. Guénon.

II. Guénon.

Pero más recientemente todavía y con motivo de la publicación consecutiva de las Memorias de Eliade, la perspectiva sobre la irradiación guenoniana se ha ampliado y así hemos tenido la oportunidad de leer un erudito artículo del estudioso italiano Cristiano Grottanelli, bajo el acápite de «Mircea Eliade, Carl Schmitt, René Guénon, 1942», en la Revue de l’Histoire des Religions Tome 219, fascículo 3, julio-septiembre 2002, pp. 325-356, que arroja nuevas luces y sombras sobre la cuestión claramente anticipada en el título y que amplia el panorama con la mención del gran jurista y experto en derecho internacional, Carl Schmitt, tan apreciado en los comienzos de los años 30 por el régimen nacionalsocialista, como posteriormente repudiado tanto por la SS y el nazismo que representaban, como por sus vencedores aliados.

Pero más recientemente todavía y con motivo de la publicación consecutiva de las Memorias de Eliade, la perspectiva sobre la irradiación guenoniana se ha ampliado y así hemos tenido la oportunidad de leer un erudito artículo del estudioso italiano Cristiano Grottanelli, bajo el acápite de «Mircea Eliade, Carl Schmitt, René Guénon, 1942», en la Revue de l’Histoire des Religions Tome 219, fascículo 3, julio-septiembre 2002, pp. 325-356, que arroja nuevas luces y sombras sobre la cuestión claramente anticipada en el título y que amplia el panorama con la mención del gran jurista y experto en derecho internacional, Carl Schmitt, tan apreciado en los comienzos de los años 30 por el régimen nacionalsocialista, como posteriormente repudiado tanto por la SS y el nazismo que representaban, como por sus vencedores aliados. En vísperas de Navidad del mismo año Eliade recibió Tierra y mar de parte de Schmitt, y Goruneanu le informa que el número 3 de Zalmoxis que había enviado a Schmitt lo acompañaba a Jünger en su mochila. Y esta triple relación de personas, directa, en un caso, e indirecta en el otro – por medio de la revista Zalmoxis-, se repite en 1944 y posteriormente. El primer caso se concretó por un nuevo encuentro de Schmitt -quien consideraba a Guénon: “El hombre más interesante de su tiempo” según señala Eliade en Fragmentos de Diario- con éste en Lisboa. En la visita de 1942, conjetura Grottanelli, de acuerdo con los testimonios de una simpatía recíproca de ambos personajes sobre Guénon, conversarían sobre él posiblemente no sólo como maestro sino también como teórico de la Tradición. El segundo encuentro a que nos hemos referido de Jürgen y Eliade y que nos interesa menos en este trabajo, llevó a que un tiempo después Jünger y Eliade dirigieran la revista Antaios.

En vísperas de Navidad del mismo año Eliade recibió Tierra y mar de parte de Schmitt, y Goruneanu le informa que el número 3 de Zalmoxis que había enviado a Schmitt lo acompañaba a Jünger en su mochila. Y esta triple relación de personas, directa, en un caso, e indirecta en el otro – por medio de la revista Zalmoxis-, se repite en 1944 y posteriormente. El primer caso se concretó por un nuevo encuentro de Schmitt -quien consideraba a Guénon: “El hombre más interesante de su tiempo” según señala Eliade en Fragmentos de Diario- con éste en Lisboa. En la visita de 1942, conjetura Grottanelli, de acuerdo con los testimonios de una simpatía recíproca de ambos personajes sobre Guénon, conversarían sobre él posiblemente no sólo como maestro sino también como teórico de la Tradición. El segundo encuentro a que nos hemos referido de Jürgen y Eliade y que nos interesa menos en este trabajo, llevó a que un tiempo después Jünger y Eliade dirigieran la revista Antaios. Nuevamente en este texto transparente están reunidas por Eliade las dos puntas de su posición de aceptación y crítica en relación con Guénon y otros autores vecinos por las ideas: simbolismo e ideas tradicionales garantizadores de la universalidad de las creencias sagradas como fondo organizador, pero a partir de la investigación científica. El reunir y avecinar documentos no es erudición positivista ni vacía, sino que en el allegamiento surgen ante la mente sensible y perspicaz a los fenómenos aproximadamente las ideas y principios transcendentes que subyacen. Las hierofanías, como manifestaciones de lo sagrado, revelan uniones o integraciones mediadoras que ligan a los contrarios –lo profano y lo sagrado- con equilibrio, lo organizan en sistemas estructurales en el lenguaje del símbolo y del mito, y permiten al alma religiosa arcaica y actual ascender a los orígenes constitutivos. No hay una diferencia insalvable acerca del reconocimiento del fondo espiritual entre Eliade y Guénon, sí lo hay en cuanto al método de acceso. Firmeza de la tradición y de la iniciación en cuanto a Guénon, ingreso por el reconocimiento de los fenómenos sagrados reflejados en la conciencia que cada vez exigen mayor comprensión, para Mircea Eliade. Guénon aspira a romper con lo profano para tener acceso no reflejo, sino directo a lo sagrado; Eliade, se sumerge en la dialéctica de lo sagrado y lo profano que acompaña a la vida del cosmos y la sociedad. Lo primero da una existencia digna de iniciados; lo segundo, de hombres en el mundo vitalmente sacro, que eligen diferentes destinos.

Nuevamente en este texto transparente están reunidas por Eliade las dos puntas de su posición de aceptación y crítica en relación con Guénon y otros autores vecinos por las ideas: simbolismo e ideas tradicionales garantizadores de la universalidad de las creencias sagradas como fondo organizador, pero a partir de la investigación científica. El reunir y avecinar documentos no es erudición positivista ni vacía, sino que en el allegamiento surgen ante la mente sensible y perspicaz a los fenómenos aproximadamente las ideas y principios transcendentes que subyacen. Las hierofanías, como manifestaciones de lo sagrado, revelan uniones o integraciones mediadoras que ligan a los contrarios –lo profano y lo sagrado- con equilibrio, lo organizan en sistemas estructurales en el lenguaje del símbolo y del mito, y permiten al alma religiosa arcaica y actual ascender a los orígenes constitutivos. No hay una diferencia insalvable acerca del reconocimiento del fondo espiritual entre Eliade y Guénon, sí lo hay en cuanto al método de acceso. Firmeza de la tradición y de la iniciación en cuanto a Guénon, ingreso por el reconocimiento de los fenómenos sagrados reflejados en la conciencia que cada vez exigen mayor comprensión, para Mircea Eliade. Guénon aspira a romper con lo profano para tener acceso no reflejo, sino directo a lo sagrado; Eliade, se sumerge en la dialéctica de lo sagrado y lo profano que acompaña a la vida del cosmos y la sociedad. Lo primero da una existencia digna de iniciados; lo segundo, de hombres en el mundo vitalmente sacro, que eligen diferentes destinos.

Die State University of New York Press hat die englische Übersetzung des „portugiesischen Tagebuchs“ (Jurnalul portughez) von Mircea Eliade – er war von 1941-45 rumänischer Botschafter in Lissabon – veröffentlicht:

Die State University of New York Press hat die englische Übersetzung des „portugiesischen Tagebuchs“ (Jurnalul portughez) von Mircea Eliade – er war von 1941-45 rumänischer Botschafter in Lissabon – veröffentlicht: Evola hat 1942 „Il filosofo mascherato“, die Besprechung eines Buches von Maxime Leroy über Descartes’ deviantes Rosenkreuzertum und seine Rolle im Rahmen der Gegeninitiation, in „La Vita Italiana“ veröffentlicht. (Deutsche Übersetzung: Der Philosoph mit der Maske, in: Kshatriya-Rundbrief, Nr. 7, 2000) Schmitts „Leviathan“ besprach Evola bereits 1938 in „La Vita Italiana“ (nachgedruckt in zwei weiteren wichtigen italienischen Zeitschriften). Evola kommt im übrigen in Eliades Tagebuch laut Index nicht vor.

Evola hat 1942 „Il filosofo mascherato“, die Besprechung eines Buches von Maxime Leroy über Descartes’ deviantes Rosenkreuzertum und seine Rolle im Rahmen der Gegeninitiation, in „La Vita Italiana“ veröffentlicht. (Deutsche Übersetzung: Der Philosoph mit der Maske, in: Kshatriya-Rundbrief, Nr. 7, 2000) Schmitts „Leviathan“ besprach Evola bereits 1938 in „La Vita Italiana“ (nachgedruckt in zwei weiteren wichtigen italienischen Zeitschriften). Evola kommt im übrigen in Eliades Tagebuch laut Index nicht vor.